SAR Archaeological Studies

Cultural Traces in the Wadden Sea

In Medieval times, the German North Sea coastline was very different from how it is today: the North Frisian islands did not yet exist, but were still what was called the ‘Uthlande’ (outer lands) and what was part of, or connected with, the mainland. Vast areas along the coast were dominated by swamps, marshes, and swamp forests, which often made any settlements difficult or impossible. In the sparse settlements on the German North Sea coast houses were often built on dwelling mounds, protected by small dikes (the latter being called ‘summer dikes’, because they could effectively provide protection against high water only during summer, when there are usually no storms). Systems of drainage ditches were built to remove the water from the farmlands, thereby allowing for any kind of agriculture.

On January 16, 1362, after more than 24 hours of severe westerly storm, an immense storm tide flooded the coast, causing the small dikes to break at many places, and eventually causing the death of a great number of cattle and men. As a result of that storm surge, which is known in history as the Saint Marcellus’ Flood or ‘Grote Mandrenke’ (‘great drowning of men’), huge land areas were lost to the sea, and they haven’t been diked ever since (compare the upper and middle panels of Figure 1). Thereafter, it took a long time until new dikes were built to protect the remaining marsh land. The new farmland was characterized by wider plots of land, the dikes enclosed larger polders than in the centuries before, and farmhouses on terps were connected by narrow lanes.

Another major storm surge occurred on October 11, 1634, again killing cattle and men, after the dikes had broken at many places. This second ‘Grote Mandrenke’ (also known as Burchardi Flood) hit the area of North Frisia in an economically weak period, after the plague had caused many deaths only about 30 years before. The island of Strand, in the center of the North Frisian coast, was cut into parts by the flood (compare the middle and lower panels of the figure below), thereby destroying farmland, farms, and whole villages. The Burchardi Flood is still the most-known storm surge in history in the area of the North Frisian Wadden Sea.

Changes in the German North Sea coastline during the past 700 years, after Behre (2009).

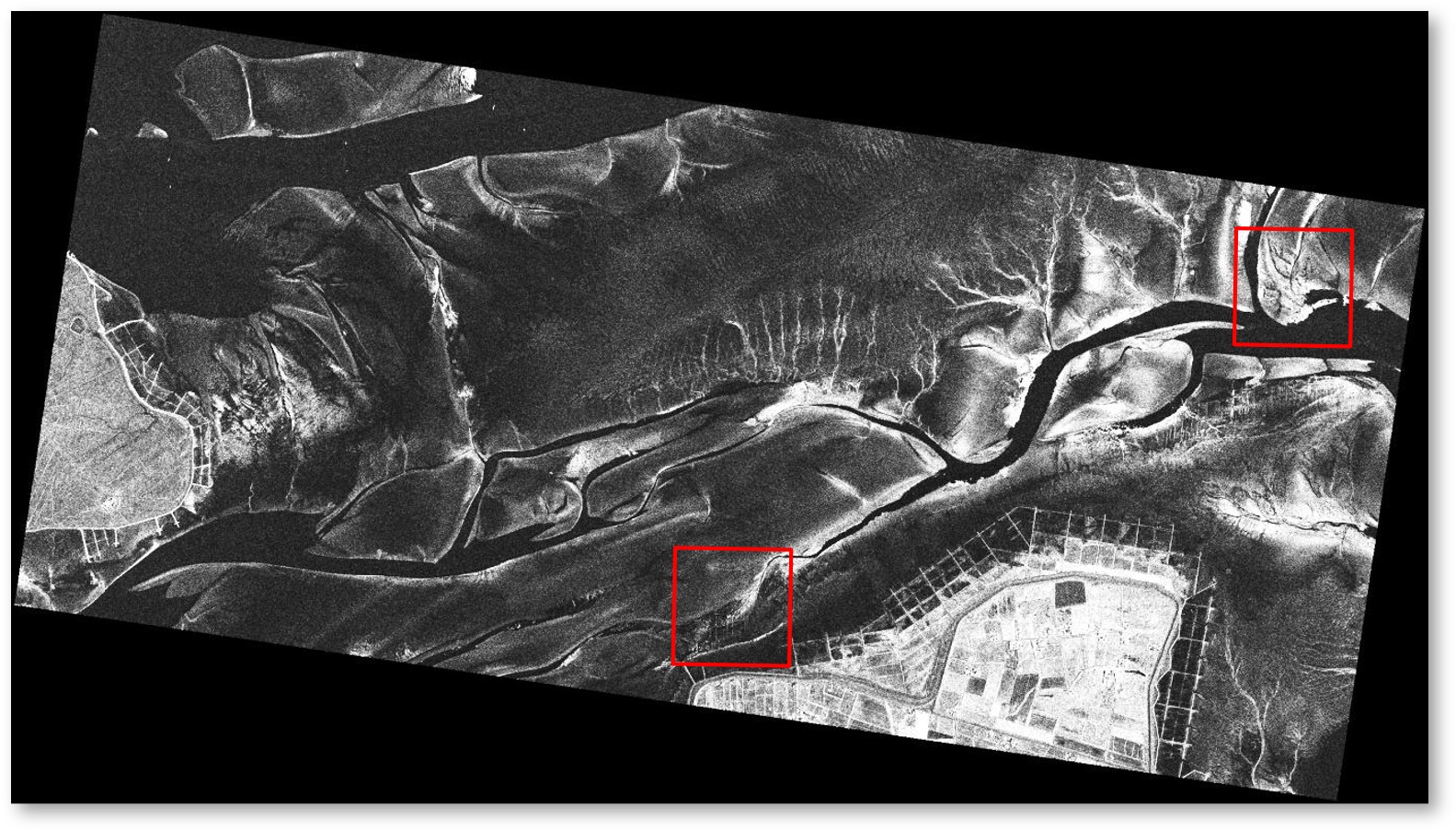

A TerraSAR-X image (11.6 km × 5.2 km) of that area, acquired on December 12, 2012, (at 05:33 UTC, 18 minutes after low tide), is shown below. The islands of Pellworm and Hooge can be seen in the lower and left parts of the image, respectively, and tidal channels and creeks show up dark, because of the low wind speed during image acquisition (4 m/s, blowing from SE; the radar backscattering mainly depends on the roughness of the water surface; therefore, a flat surface at low wind speeds causes low radar backscatter and, thus, dark image areas). The bright features in the right half of the image mark edges of tidal creeks and dry, sandy sediments, but are not of interest herein. However, in the two (1.0 km × 1.0 km) areas marked by the white squares, we found fine, linear structures, which are due to remnants of former land use (before the storm surge of 1634).

TerraSAR-X image of the area of interest, north of Pellworm and east of Hooge. The image was acquired on 12 December 2012. The red squares denote the same locations as in Figure 3. © DLR 2012.

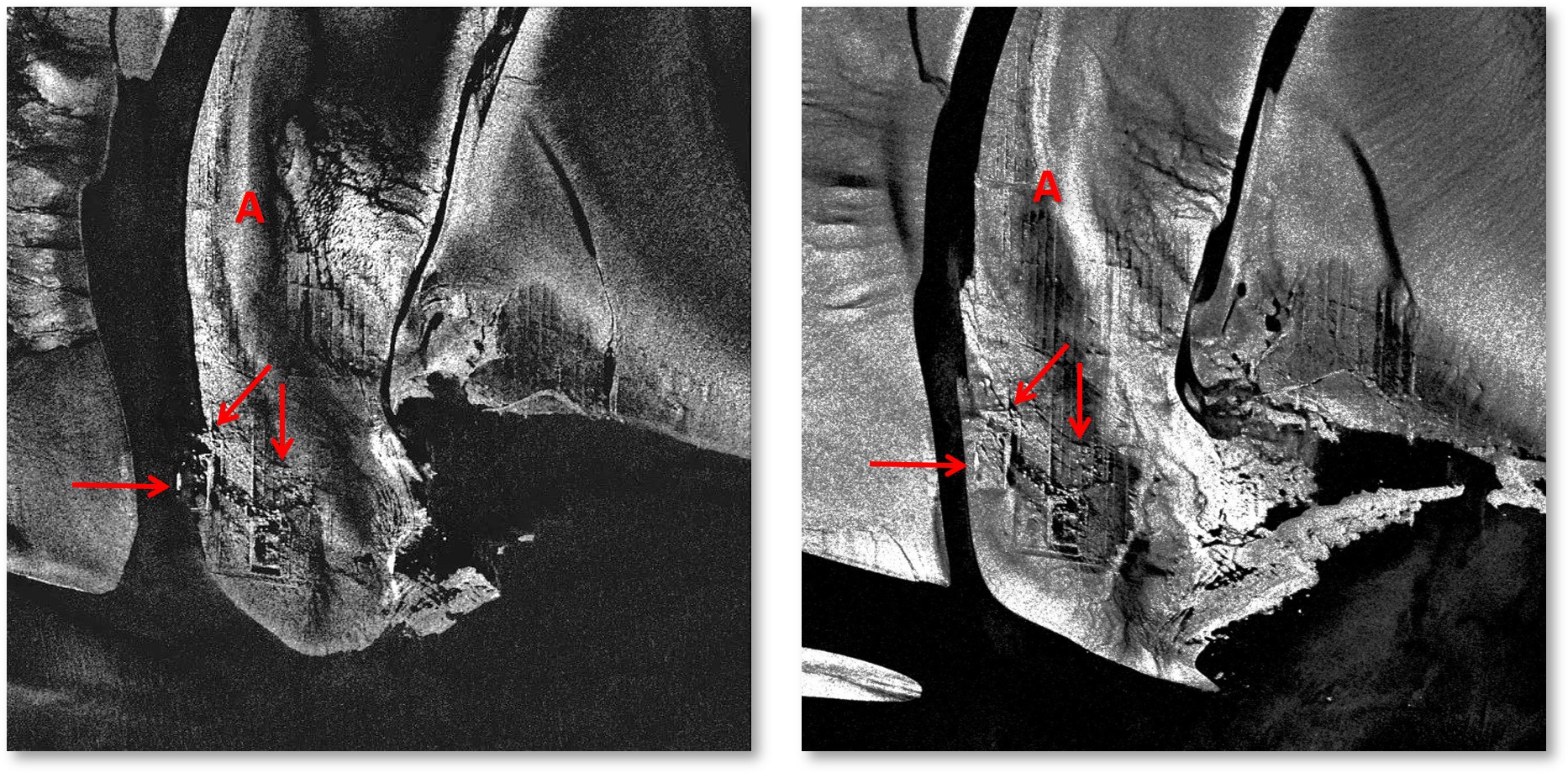

The next figure contains 1000 m × 1000 m details of two TanDEM-X images acquired in staring spotlight mode on November 19, 2014, at 17:01 UTC (left panel; 26 minutes after low tide, 3 m/s wind from easterly directions) and on January 20, 2015, at 05:50 UTC (right panel; 37 minutes before low tide, 1.3 m/s wind from easterly directions), respectively, and shows examples of such structures. The location of these 1 km² details is marked by the upper right square in the above figure. The very fine pixel sizes of 26 cm × 26 cm and 28 cm × 28 cm, respectively, allow imaging of residuals of historical land use (houses, ditches, lanes), which usually are too narrow to be delineated on SAR imagery of conventional resolution (with pixel sizes on the order of 10 m).

Subsections (1000 m × 1000 m) of two TanDEM-X staring spotlight scenes acquired on 19 November 2014 (left) and 20 January 2015 (right), north of Pellworm. The linear structures are cultural traces. The letter (A) and the arrows are inserted for comparison. © DLR 2014, 2015.

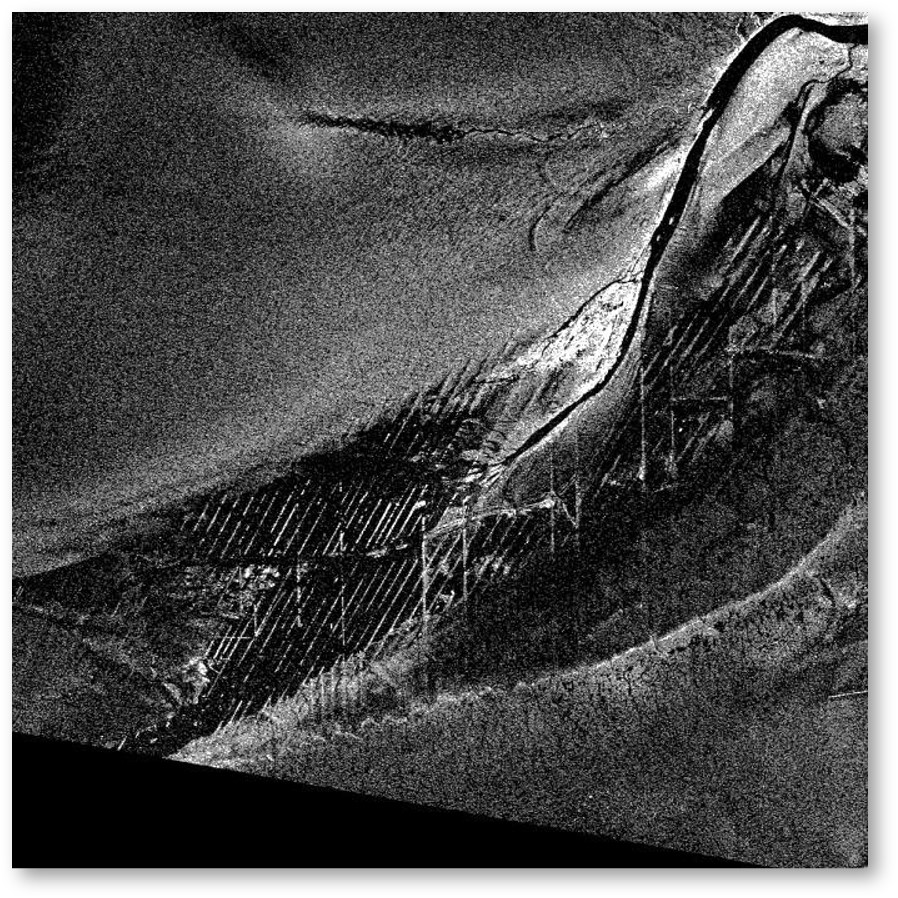

Another example of very high resolution SAR imagery of archaeological sites is shown in the next figure. The small section (again, 1000 m × 1000 m, corresponding to the lower left square in the uppermost SAR image) of a TanDEM-X staring spotlight scene was acquired on November 21, 2014, at 05:41 UTC (low tide; 2 m/s wind from easterly directions) and shows many bright and dark parallel lines all over the image center. The distance of those lines is between 10 m and 20 m, again, indicating that they are remnants of a former mesh of draws and ditches built for the drainage of the farmland. The ditch residuals are marked by denser (harder) sediment causing higher surface roughness which, in turn, results in higher radar backscattering. However, we also note that, once the space in between is partly filled with sandy sediments, some of the lines may also appear dark (seen in the image center).

. Subsection (1000 m × 1000 m) of a TanDEM-X staring spotlight scene acquired on November 21, 2014, north of Pellworm island and showing remnants of historical drainage systems. © DLR 2014.

In many cases, the observed signatures of former ditches are due to different sediment types, which in turn are due to the actual ditch morphology. Fossil roots and other organic material may result in denser and harder sediments, which may be directly sensed by the space borne SAR, or which may cause additional sedimentation (i.e., deposition of sandy sediments) that can be seen on SAR imagery. We also note that different sediments may cause different biological productivity, and are therefore often marked by benthic organisms, which may cause different surface roughness patterns. It is those patterns that are sensed by the high-resolution X-Band SAR.

Reference:

Behre, K.-H., 2009: Landschaftsgeschichte Norddeutschlands: Umwelt und Siedlung von der Steinzeit bis zur Gegenwart. Wachholtz, Neumünster, 308 pp.

Theses, Publications

Gade, M., J. Kohlus, and C. Kost, 2017: SAR Imaging of Archaeological Sites on Intertidal Flats in the German Wadden Sea, Geosci. 7, 105; doi:10.3390/geosciences7040105.

- Gade, M., J. Kohlus, and C. Mertens, 2017: Archaeological Surveys on the German North Sea Coast Using High-Resolution Synthetic Aperture Radar Data. Proceed. 37th Intern. Sympos. Remote Sens. Environ. (ISRSE37), Tshwane, South Africa, 8 - 12 May 2017.

- Gade, M., and J. Kohlus, 2016: After the Great Floods: SAR-Driven Archaeology on Exposed Intertidal Flats. Proceed. ESA Living Planet Symp. 2016, Prague, Czech Republic, 9-13 May, 2016.

- Gade, M., and J. Kohlus, 2015: SAR Imaging of Archeological Sites on Dry-Fallen Intertidal Flats in the German Wadden Sea, Proceed. Intern. Geosci. Remote Sens. Sympos. (IGARSS) 2015, Milan, Italy, 27-31 July 2015.

To get to the internal pages click here.

To get to the internal pages click here.

.. back to the KFEW3O page ...

.. back to the KFEW3O page ...